Iconic photos of Walter Payton and Matt Suhey have been blessing and curse for local photographer

You can thank Jim Maentanis, who was just a clueless, freelancing 21-year-old college kid, for the pics from the Bears minicamp in 1985.

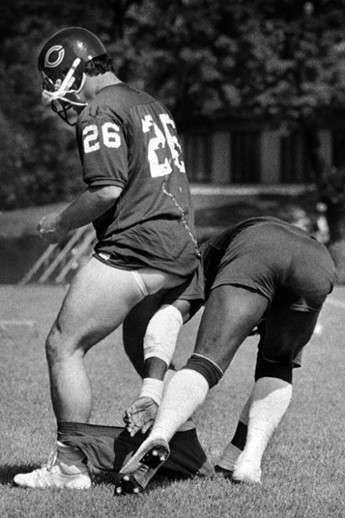

OK, I defy anybody to sit calmly and study the three-photo sequence of Walter Payton ‘‘pantsing’’ Matt Suhey in the spring of 1985 and not crack up.I can’t.

And I’ve been looking at the photos off and on for days. Payton’s got Suhey’s shorts by the wee tip of his finger in the first photo, like a kid launching a slingshot.

He’s more determined in the second photo, having brought both hands into play. And, good Lord, look at the devilish semi-grin he’s not bothering to hide. Payton, prankster eternal, is in his wheelhouse in the I-formation, going for the kill.

And — wait for it — here it is:

No. 3 shows fullback Suhey’s shorts around his ankles as his

Hall of Fame halfback/pal completes the mission.

This series never has been published in its entirety before, and

we have photographer to thank for that courtesy today.

Honestly, folks, if you’ve been having a bad week or are feeling

stressed out or put upon, this glimpse at nitwit, lowbrow humor as practiced by

perhaps the most beloved yet tragically departed Chicago sports hero of all

time is a pick-me-up supreme. And you can thank Maentanis, who was just a

clueless, freelancing 21-year-old college kid back then, for the pleasure.

Think about it.

First of all, you can’t do this kind of thing in public anymore.

The decency police or the players’ union or Mothers Against Bare Buttocks would

be swarming with outrage and summons and perhaps probation for Payton as a

first-time offender (even though he was a serial wisenheimer).

Plus, nobody would do this to anybody but a good friend. Payton

and Suhey were best buds, a kind of unmixed chocolate-and-vanilla gridiron

cupcake. Payton was the black kid from the Deep South by way of little Jackson

State; Suhey was the white boy from Pennsylvania via Joe Paterno and mighty

Penn State.

Payton was the dancing Bear; Suhey was the bowling ball clearing

the path. Their affection for each other would become clearest when Payton was

dying of liver cancer and Suhey was there to soothe his friend and run

interference for him against the swarming media horde.

That friendship is subversively embodied in these shots. After

all, Suhey is protecting his bare cheeks with one useless hand, remaining in

his stance rather than turning around and belting the ruthless Payton. Life was

fun and impertinent back then, and football, brutal game that it was, still had

room for silliness. Maybe it wasn’t ever really so, but that’s how we can

imagine it. That’s how it seemed. That’s how time passes, how life moves on,

how the photos play out.

Indeed, frozen here like two bawdy comedic actors, Payton and

Suhey represent something oddly humanizing and comforting about the vicious

game.

Remember, this isn’t some run-of-the-mill halfback stretching a

teammate’s elastic. It’s the greatest player in Bears history, one of the

greatest in football history, the man whose name is emblazoned on the NFL’s Man

of the Year Award, the trophy given annually to the player whose volunteer and

charity work matches his excellence afield.

You also better get a chuckle out of this: Athletes actually

wore jock straps back then. I don’t know if they even sell such things anymore.

Well, yes, they do. With names such as ‘‘Midnight Pop,’’ ‘‘Cowboy’’ and

‘‘Massive Night Sparkle Bubblebutt.’’ Couldn’t make those up, people. They’re

not, uh, sports jock straps, though.

Compression shorts are the undergarment deal in sports these

days. So you know what pantsing your teammate would look like now? Replacing

one pair of shorts with another.

As with any great photograph, there’s a story behind these.

And this is all about Maentanis, a Glenview native who was a

walk-on football player at Southern Illinois University, a tremendous fan of

the Bears and home for spring break in March 1985. Unfortunately, his story as

it relates to the imagery isn’t all sunshine and rainbows.

As we sit at a suburban coffee shop and he lays out the details

of the shoot of 34½ years ago and the history of his photography career,

Maentanis tells the tale of how a nearly accidental moment of transcendence

changed his life in ways he never could have expected. Now 56 and unemployed,

Maentanis sometimes gets so bogged down in details leading up to and away from

that football practice that he says things such as: ‘‘I’m sorry. If I’m

off-track, just tell me and I’ll stop.’’

What he’s very clear about is how the Payton-Suhey photos came

to pass.

The Bears were having a minicamp at their facility in Lake

Forest, a beat-up grass field they shared with the Division III Lake Forest

College Foresters (how times have changed!), and Maentanis took three of his

buddies from now-closed Maine North High School — brothers Bobby, Billy and

Walt

Cohen — with him to check things out. Why did the brothers come

along?

‘‘The Bears!’’ Maentanis said.

Enough said.

He also took his camera — a Nikon F3 with a couple of lenses —

because ‘‘my camera went everywhere with me.’’

Having studied photography for four years in high school and

continuing with it at SIU, Maentanis was taking shots for the college

newspaper, as well as stringing for the Southern Illinoisan, the

25,000-circulation newspaper in Carbondale. All his life, he had wanted to be

one of two things: a pro football player or a professional photographer.

The football thing wasn’t going to work out. A sturdy 6-1

receiver with good hands who eventually won a scholarship, Maentanis

nevertheless was so slow afoot that ‘‘the cheerleaders were faster than me,’’

he said.

Plus, his photo assignments for class conflicted constantly with

afternoon practices. So photography it was.

On this day, however, he wasn’t on assignment for anyone. He was

just a fan, looking for Payton, his hero.

‘‘We went into the practice, and the brothers stayed with

spectators,’’ Maentanis said. ‘‘I went over to where the running backs were

lined up.’’

There were no cops holding people back and no tickets needed. It

was just a warm, sunny football day open to the public, years before

social-media mayhem or the horrors of 9/11 and rampant serial shootings. The

Bears were an open book.

As he was seeking out Payton, Maentanis fitted into his camera a

180 2.8-millimeter lens, a fixed, fast telephoto lens that could give him good

depth of field and detail from yards away. He looked up, and Payton already had

grabbed Suhey’s shorts and let them fly.

‘‘Oh, no,’’ he thought. ‘‘I missed a great shot!’’

But then Payton did it again. And again. For 10 or 15 minutes.

He was motivated.

‘‘All the guys were laughing,’’ Maentanis recalled. ‘‘Suhey kept

on yelling at Walter to stop, but he wasn’t mad. This was hilarious.’’

Maentanis stepped inside the rope that separated the sideline

from the field and fired off some photos of the drill out in the center of the

field. Ken Valdiserri, the Bears’ director of marketing and broadcasting,

abruptly walked out and asked him what he was doing, how he thought he could

waltz out onto the field. Maentanis told him whom he was and that he was doing

some freelance work. It was all true, but it was somewhat beside the point,

given he was also just a college kid on break ogling his heroes and doing what

he had asked no one permission to do.

Valdiserri got Maentanis back on the sideline, and the practice

ended not long after that. Valdiserri was speaking with Suhey about some other

matters near midfield when Payton crept up and, crouching low, yanked down

Suhey’s shorts once and for all. That’s the third photo in the series,

the fait accompli. If it weren’t cropped just so, Valdiserri would

be seen on the left border, amused like everyone else.

‘‘If this had all been on video, it would have been so funny,’’

Maentanis said. ‘‘They’d get in position, and Suhey would scoot up a few inches

to get out of Walter’s grip. He was yelling, ‘Knock it off!’ The audio would

have been great.

‘‘On one of the shots, I didn’t even have time to focus; I just

fired. Another one, I had to back up a few steps to get it. But Payton kept

doing it over and over again, messing around. Then Suhey was talking to Kenny,

and I saw Payton sneaking up, and that was the end.’’

The weird thing about photography years ago was that it was all

done on film, which the cameraman had to rewind himself, put into a tiny

cylindrical container and send to a darkroom for development. Nobody knew what

he had until the negatives came out and prints were made. The idea of digital

images instantly viewable was crazy.

The suspense between shooting and the image garnered could be

almost unbearable. Indeed, anything could ruin the undeveloped film — heat,

cold, water, light, X-rays, a teething dog — and the film might be bad or

exposed even before it was loaded into the camera. And the camera might not

load the film at all. These were things photographers found out with depressing

regularity.

Maentanis had no idea what he had captured, if anything, until

he drove back to SIU and got his single roll of black-and-white film developed.

What was there was pretty good, pretty funny. In fact, it was quite good and

funny. He showed it to the editors at the Southern Illinoisan.

‘‘They all liked it, and they laughed,’’ Maentanis said.

But the photos never ran, not there or anywhere. The reason?

Don’t laugh.

‘‘They said, ‘It’s too risqué,’ ’’ he said.

And so it went for many years. Maentanis made a few copies and

gave them to pals, and he had Payton and Suhey sign some for him. But he didn’t

monetize anything. He wasn’t an entrepreneur of any kind.

The Bears would win the Super Bowl 10 months after that

minicamp, and names such as Ditka, McMahon, Singletary and The Fridge became

household words. Payton

already was a legendary figure, but there was a lingering

sadness to that Super Bowl XX victory, an annihilation of the Patriots that

should have been pure joy.

Suhey scored the first touchdown in the Bears’ 46-10 rout.

Quarterback Jim Mc-

Mahon scored two touchdowns. Defensive back Reggie Phillips

scored on an interception return. Backup defensive tackle Henry Waechter

recorded a safety. Even William ‘‘The Refrigerator’’ Perry scored.

But Payton did not. And for a proud and sensitive man with a

warrior’s ferocity and a child’s heart, that was damaging. All of a sudden,

that Payton-Suhey photo had turned into something different, a talisman from a

more innocent time.

The defining quality, however, came some 14 years later, when

Payton died of a devastating liver disease. Only 45, he was gone too soon, and

everyone knew it. This month marks the 20th anniversary of Payton’s death, and

it was only a couple of months

ago that the Bears unveiled the large bronze statue of Payton

that stands in front of Soldier Field, not far from the new statue of Bears

founder George Halas.

†††

It was three years after the Super Bowl victory or thereabouts

that Maentanis’ dad, a former deputy sheriff, was working security at a charity

auction. He called his son and told him he ought to donate one of his photos to

the cause. Maentanis did, and the photo sold for $500.

‘‘That was it,’’ he said. ‘‘My mom said: ‘You got something

there. Maybe you should think about doing something with it.’ But

licensing stuff and all that, it was difficult. I was

freelancing in Florida at the time, and I wouldn’t get back to the Midwest, to

a job in Wisconsin at the Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, until 1997.

“And then in early 1999, Walter announces he’s sick. And on that

day, Feb. 2, my photo went out on the AP wire for the first time. And the next

thing I know, it went crazy.

Everybody was calling about the photo. It was in newspapers

across the country. People magazine called and bought it, and it ran in the

Richard Gere ‘Sexiest Man Alive’ cover issue.’’

Maentanis had a deeply respectful love for Payton that he

carries to this day. Much of it started when he was visiting a high school

girlfriend who lived in Arlington Heights. They were sitting on her steps on a

hot summer day when an African American man in a ripped T-shirt went running

past.

‘‘Who’s the Charles Atlas bodybuilder guy?’’ Maentanis asked,

marveling.

He couldn’t believe it when his girlfriend said it was Payton.

‘‘And he lives across the street,’’ Maentanis said. ‘‘Like, if

this is 12 o’clock straight ahead, his house was at 10 o’clock. My jaw dropped.

Then he slowed down and said, ‘Hi, Ellie!’ and he came by and talked to her and

asked if I wanted to play basketball. I freaked.’’

So they played hoops a number of times that summer on Payton’s

driveway basket, with Payton’s Lamborghini moved safely out of the way. The

5-10 Payton sometimes was able to dunk the ball, which amazed Maentanis. Quite

often, 4-year-old Jarrett Payton would watch the action.

‘‘A couple of times, [Payton’s wife] Connie would bring us

lemonade,’’ Maentanis said. ‘‘And I remember one time holding Jarrett on my

lap. I’m saying to myself, ‘I’m holding Walter Payton’s son!’ ’’

On the day of the minicamp photograph, Maentanis wanted to tell

Payton who he was, that they were old hoops buds, but he never got the chance.

After Payton’s death, he wanted to honor Payton by using the photo or photos to

raise organ-donor awareness, something Payton himself had promoted passionately

in his final year, as he waited for a liver transplant that might extend his

life.

The transplant never happened, but Maentanis arranged a deal

with the secretary of state’s office to give away free copies of the photo at

charity events to anyone who signed up for or showed interest in signing up for

organ-donor status.

‘‘You know how powerful Walter’s message was?’’ Maentanis said.

‘‘Illinois went from being 47th in the country — basically last — in people who

signed up to be organ donors to first in only a few months. I set up tables and

gave the photos away for free. I couldn’t make people pay or demand they sign

the donor cards, but I did get thousands of people to sign their names, and

then I’d send them to the secretary of state.’’

The charity was nice, but it didn’t help Maentanis’ financial

prospects. Photography is a dying business. Or, rather, it’s an

exponentially expanding business — non-profit, for sure —

because every human out there with a modern phone is a photographer for free.

Just as the internet is free, so are the

images people can download — both legally and illegally.

Maentanis has found his photos being used in restaurants, in videos, on CDs, in

documentaries, on posters, at memorabilia conventions, just about any way and

everywhere football fans might want to see them. He can sue — and he has — but

it’s exhausting, and the damages are small.

There is a legal thing called ‘‘fair usage,’’ wherein a

filmmaker or documentarian can use almost any image without paying for it,

provided there is a defensible educational aspect to the work and there is no

real profit being made. It is a vague and complex law with obvious benefits for

the public, in general, but it can be a nightmare for a starving artist or

creative individual to battle against.

To some extent, Maentanis has lost out on what he captured with

his camera because he chose certain non-mercenary pursuits over moneymaking

things. For example, he cared for his mother for a half-dozen years until she

died a year ago, making a full-time job impossible.

He still has a letter from April 8, 1991, from late sportswriter

and sportscaster Tim Weigel, who apologized for being unable to transfer a tape

to VHS for Maentanis of Channel 7 reporter Brad Palmer and Payton holding up

one of Maentanis’ photos during a broadcast.

‘‘Sorry it didn’t work out, but I still have the picture framed

and on my desk here at Channel 7,’’ Weigel wrote. ‘‘Whenever I look at it, I

think of you.’’

That means something, doesn’t it? Even if Weigel himself died

far too young of a brain tumor in 2001, the thought was there.

Nothing is ever quite what it seems, anyway. Jeff Pearlman’s

2011 biography of Payton, ‘‘Sweetness: The Enigmatic Life of Walter Payton,’’

showed that the man was anything but the simple, one-dimensional, childish nice

guy and prankster he often was made out to be.

Pearlman described Payton as having drug addictions for his

football pains and being buffeted by suicidal thoughts, with longtime agent Bud

Holmes stating: ‘‘Walter would call me all the time saying he was about to kill

himself. He was tired. He was angry. Nobody loved him. He wanted to be dead.’’

I know Pearlman and respect him, and I remember well when he

came to Chicago on the book tour and told me he was amazed that he was cast as

the bad guy by locals for bearing bad news, that his book was

reviled, that simply by telling the truth he was dismissed and

disparaged for casting doubt upon a civic icon. I told him he didn’t know how

important an untarnished Payton was to the populace here, that it almost defied

explanation. I couldn’t explain it myself — and this coming from a fellow who claims

to champion the truth — but I felt it all the same. A flawed football star gave

us everything he had, and we took it. And when that star was demeaned, so were

we.

This drifts into the esoteric, the philosophical. And parts of

it all haunt Maentanis to this day. There are these lighthearted photos from

many years ago that somehow got away from him and became almost a curse. Which

is so wrong, so sad.

‘‘If you’re not marketing- or business- savvy, everybody steals

from you,’’ he said. ‘‘In a way, the photos have been a nightmare of my life.

But complaining won’t do me any good. I’m grateful I got the thousands of organ

donors, that it makes people happy. But otherwise . . . ’’

He pauses here. So much time has gone by. So many things have

changed. Can a smile fade to gray? Can a cheerful image mutate the way the rest

of life so often does? Is a photo ever really that important?

‘‘Otherwise,’’ Maentanis said, ‘‘I wish I never hit the

shutter.’’

No comments:

Post a Comment